Narritjin Maymuru was born in approximately 1912 in Manggalili country, between Caledon Bay and Blue Mud Bay, on the western shores of the Gulf of Carpentaria. In this area he lived until his twenties when he travelled north to Yirrkala, to the newly established mission there. Until then, he led a fully tribal life, knowing no other law than the ‘old law’, and hunting with his relatives using traditional stone tipped spear and woomera. He would also have participated in whatever ceremonies were appropriate to his age grade. He was a great warrior and in 1932 was involved in the massacre of the Japanese pearlers at Caledon Bay.

He has remained intimately involved with his culture and has been a powerful force in holding the Manggalili Clan together in the Yulngor tradition. When the bauxite mining company moved into Melville Bay area, he was most concerned about the violation of his country and, through his mission-educated son, wrote a letter of protest to Mr. Harry Guiese, Director of Aboriginal Welfare. Narritjin travelled the 500 or so miles to Darwin, living off the land and swimming crocodiles and shark infested rivers, to finally hand the letter to Mr Guiese in his office.

Today the wheel has turned full circle and Narritjin; with other members of his clan, are busily engaged in re-establishing themselves in their old ‘country’ at the Manggalili outstation at Djarrakpi on Cape Shield.

Bark paintings are significant to clan members in many different ways. As well, in the clan designs the patterns are interwoven with the ownership of chants, dances and mythology, some are stylized maps of sacred sites whilst others are associated with mortuary rites. The designs are also regarded as permission from the supernatural world to occupy clan lands. They established a link between the spiritual world of the ancestral beings who created the land, and the living clan members. The designs on the paintings in this exhibition are the exclusive property of the Manggalili Clan and Narritjin Maymuru is the ‘keeper’. His permission must be obtained before another member f the clan may crate a painting and this he is entitled to do only if he ahs completed the requisite number of ceremonies. Even though Nanyin was Narritjin’s brother, he always had to ask permission before painting a bark. Narritjin says ‘the paintings are the Manggalili law, they tell us who we are and where we are going’.

Narritjin is very proud of the fact that Opossum Tree myth is one of the oldest in Arnhem Land and is ‘straight’, his words meaning that kinship laws have been strictly observed in all clan marriages, thereby avoiding any dispute about clan ownership of design.

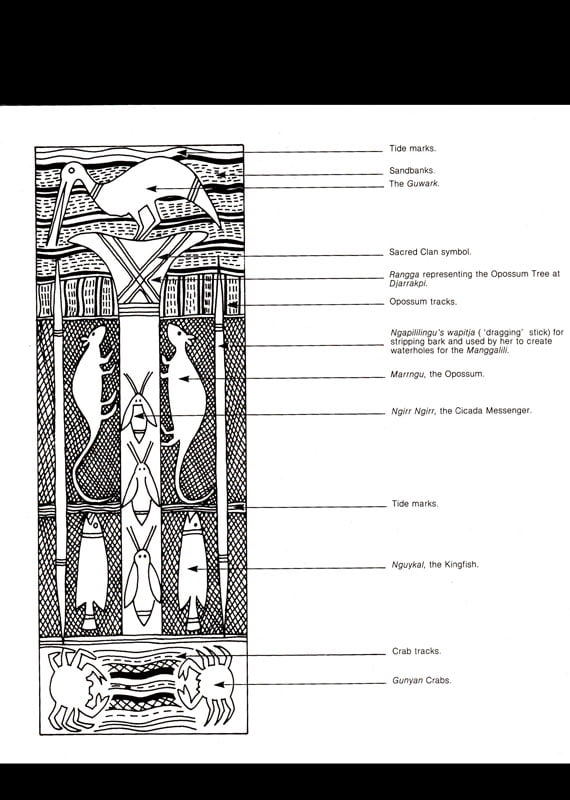

On examination of the paintings it will be observed that although they are of the Yirritja Moiety, triangular and diamond forms are only seen in a few of them. Nor do back ground designs conform to the Dhuwa specifics. In the art of the Arnhem Landers there is always the exception to the rule, and this is one of the exceptions. The design in these paintings show the tracks left by Opossum, cloud patterns on the sand dunes at Djarrakpi, tracks left in the sand by the Gunyan Crab and the parallel lines of foam left on the beach by the receding tide. These paintings are portions of the Opossum Tree mythology.

In the days of the beginning, Banaitja and Barama, with other supernatural beings, came out of the sea and the sea foam dried on their bodies and formed a diamond patterned grid. This diamond pattern they gave to the Yirritja Clans. They summoned the wise man Guwark and gave him the power to use the wings and form of a bird, to travel about the country with the spirit woman Ngapililingu to carry out the work of making the sacred places and teaching the Yulngor the correct customs.

The Possum Tree Myth

In the ‘dreaming’, the night bird Guwark became lonely and set out to find his friend Marrngu, the Opossum, to talk to. During the day he found him in several places but Marrngu would not talk to him because it was daylight. Ever since, the Guwark only calls at night as he knows this is the only time Marrngu will answer him. During his travels that day, as he flew along the coast, he saw the Kingfish Nguykai and, feeling hungry, he called out to ‘Nguykai if you will jump out of the water on to the sand I will give you some land’. Nguykai did so and was gobbled up by the Guwark. At long last he came to Djarrakpi and in the moonlight he saw the sacred tree on the cliff. As he was very tired, it was with great relief that he landed in the top of the tree and noticed the Gunyan Crabs playing in the sand at the foot of the cliff, running from their holes through parallel lines of foam left by the ebbing tide. As he sat looking about, he heard a noise and realised Marrngu was inside the hollow tree. He then sent Ngirr Ngirr, the Cicada, down the tree with a message to Marrngu who came up the tree to the Guwark and they spent there night talking about sacred places of the Manggalili. They then sent Ngirr Ngirr with a message to Ngapililingu and asked her to come with them into Manggalili country. The Opossum travelled ahead and left a path for them to follow. Before the Guwark and Ngapililingu came together at Djarrakpi, when they met at the sacred Opossum Tree (Gayawu, the Wild Cashew Tree) Guwark had already travelled extensively with Ngirr Ngirr his messenger, and named sacred places for the Manggalili. Ngapililingu is a somewhat mystical being hovering in the back ground of the mythology; information about her is very sparingly given and only after many years of contact. She taught the Yulngor women many things; how to make the paper bark water carrier, how to look for the bulb ‘yoko’ and prepare it for eating, how to make bark string and weave pandanus palm baskets. She came to the mainland from Groote Eylandt, travelling in a giant sized, bark water container with a band of specially trained spirit women known as the Warruthilaku, who eventually split up to become the different language and clan groups of the Yirritja Moiety, including Manggalili. A more important part of Ngapililingu’s work was naming flora and fauna and making them Yirritja totems, naming sacred places and making mariian. The ‘dragging’ stick (wapitja) which she made for stripping bark, is very important symbol on the bark paintings as with this she made all the Yirritja water holes.