Introduction

F rom the early 19th century, Aboriginal people created artworks that document the history of their interaction with European settlers.

Aboriginal people made boomerangs, shields, spear throwers, clubs, walking sticks, stock whip handles and other objects which they decorated with engraving, painting and pokerwork. The designs show Aboriginal links to their land and traditional cultural practices. They also depict contact situations and changing circumstances brought about by European settlement.

Focus of study

This studies main focus is the transitional art of Barambah/Cherbourg Mission. The artifacts from this area are characterized by deeply incised geometric designs and detailed depictions of humans, plants and animals. Very little is known about these artifacts. No artists names have been recorded, nor estimates of the scale of production. But they are rare – the Queensland Museum has only two similar items in its collection (QE-3344-0 and QE-12347-0).

One of the few references to the manufacture of artifacts in Barambah can be found in Thom Blake’s book Dumping Ground – A history of the Cherbourg Settlement: “Barambah inmates were involved in exhibitions and performances that were specifically designed to promote the settlement. In 1911, the Chief Protector’s Department organised a display of the various facets of its work. Each settlement and mission, including Barambah, was asked to contribute items of work by its inmates. Items displayed ranged from samples of schoolwork to traditionally made implements and weapons. In the display presented in 1913, items from Barambah included ‘fine specimens of carved whip handles and walking sticks’”.

Brief History of Barambah/Cherbourg Mission

In 1904 W.E Roth the Protector of Aborigines ordered the forcible relocation of more than 300 Aboriginal people from 13 different tribes to Barambah. Aboriginal people at Barambah were required to clear the area by hand. Early conditions in the community were so harsh, most people continued to live off the land and live in bush humpies.

In 1931 Barambah was renamed as Cherbourg. In the 1930s the government provided rations for the inhabitants and began to construct proper accommodation in the Cherbourg township. By 1934 the population was more than 900 people, representing 28 different language groups.

The settlement housed a reformatory school and training farm, a home training centre for girls, a hospital, dormitories in which the women and children lived, and churches of various denominations. Training was provided in a variety of agricultural, industrial and domestic fields. People were hired out as cheap labor and at one stage they were not allowed to leave the reserve without a permit.

Today Cherbourg is Queensland’s third largest Aboriginal community. It has developed its own strong culture and is now Aboriginal-controlled.

The effects of removal and forced assimilation of disparate tribal groups

The Queensland Government of the early 20thcentury considered any free-roaming aboriginal man or woman as lazy, idle or immoral. It pursued a policy of forced removal and segregation. Aboriginals from all over QLD and Northern NSW were gathered up and sent to Barambah, without regard for family, kinship or language groups. This amalgamation of tribal groups created disharmony and to this day, some problems still exist.

Klaus–Peter Koepping in his manuscript How to remain human in an asylum – some field-notes from Cherbourg Aboriginal Settlement in QLD relates the recollections of a woman living in Cherbourg in the 1920’s: “constant fighting with spears and boomerangs etc. occurred during that time”. Koepping also notes that the settlement police force and much of the white administration were despised and considered corrupt by the aboriginal inhabitants.

Many of the carved artifacts from Cherbourg depict the disharmony of the tribal groups and their interactions with the despised white authority figures.

Common Characteristics and Recurring Design Motifs in Cherbourg Transitional artifacts

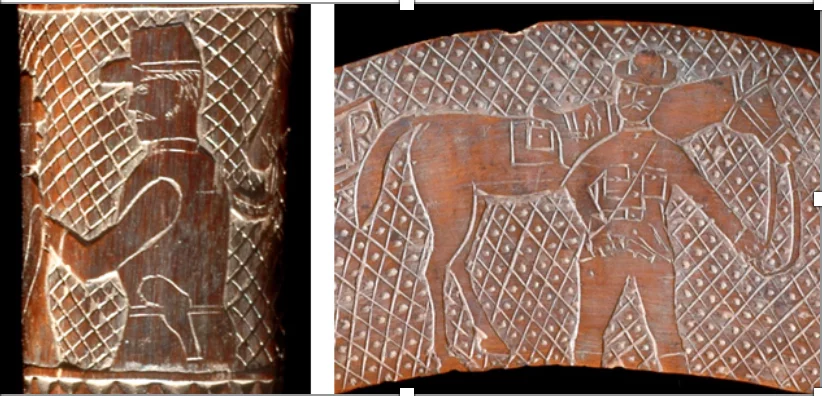

1) The “diamond and dot” background. Most of the early artifacts from Cherbourg display this type of geometric background.

2) The depictions of kangaroos and emus. These are by far the most common animals depicted on the early artifacts from Cherbourg. Other animals depicted include dingoes, crocodiles, koalas, birds, cows, echidnas and snakes.

3) The depiction of Queensland Bottle Trees (Brachychiton rupestris). These trees are found in South East QLD and were utilised extensively by Aboriginals.

The starchy tissue of the stems and roots of the bottle tree was eaten, as were the seeds. The roots yield good quantities of drinking water. The fibrous inner bark was used for making rope and twine for fishing nets.

4) Depictions of Aborigines hunting, fighting and dancing are common. They are often seen to be carrying shields, clubs and spears. These depictions may relate to the early life of Barambah mission where most aboriginal people were still living off the land and inter-tribal conflict was common

5) Depictions of authority figures. Images of police troopers, royalty, missionaries and soldiers, have been noted on several artifacts. The punitive and authoritarian nature of Barambah/Cherbourg shaped the way aboriginal people saw white people.

6) Depictions of aboriginal stockmen and horses. Horses and horse-shoes have been noted on several artifacts. Aboriginal stockmen formed the backbone of the vast pastoral industries that developed in the late 19thand early 20thcenturies. Aboriginal stockmen often had good relationships with their white “bosses”.

7) Depiction of card suit symbols. Hearts, diamonds, spades and clubs are a common motif on transitional artifacts. Poker and other gambling card games were popular with Aboriginal stockmen.

Photos of artifacts from Barambah/Cherbourg Mission

CH1 Pair of scrimshawed cow horns

Size: Both measure 28 cm in length.

Provenance: These horns came from the estate of a family on the Sunshine Coast.

The Brisbane Museum has a similar pair of horns (QE-3344-0), almost certainly scrimshawed by the same artist. The provenance on the Brisbane Museum horns states that they were acquired in 1939 but had been carved at Barambah Station / Cherbourg approximately 40 years before.

Note the depiction of the two men fighting – they appear to be wearing trousers but they also display tribal cicatrices on their chests. Also depicted is an aboriginal stockman smoking a pipe and a man in a tree, escaping from a waiting crocodile.

CH4 & CH2 Incised Boomerangs

These boomerangs (CH4 and CH2) were purchased at Sothebys Aboriginal Art sale, Melbourne 27thJuly 2004. Lots 576 and 577. The catalogue states that these boomerangs were collected by Richard “Dick” Davis, a saddler who traded artifacts for work, in Cherbourg, Queensland in 1910.

Details of CH4

Size: 66 cm.

Shows a World War 1 soldier and a lady in a “flapper” dress. This boomerang was almost certainly produced sometime between 1915 and 1920. It is not known if the soldier depicted is aboriginal or non-aboriginal. But over 400 aboriginal soldiers fought in WW1. One known Cherbourg soldier was Benjamin Combo of the 23/3rdBn. The depiction of the “flapper” lady is also interesting. Another boomerang showing “flapper” fashion has been noted – aboriginal people probably found the white fashion craze curious and amusing – in the hot and dusty environment of Cherbourg.

Close up images of CH4 are included bellow

Details of CH2

Size: 67 cm.

Shows a corroboree and aboriginals returning to their campsite. This very detailed boomerang show what life may have been like at Barambah Mission prior to 1920 – bush humpies, traditional hunting and foraging and ceremonial dancing.

Close up images of CH2 are included bellow

CH5 & CH6 Incised Boomerangs

These two beautiful boomerangs (CH5 and CH6) represent the acme of Cherbourg transitional art. They are both incised in great detail and show interesting vignettes of life in early Barambah/Cherbourg.

Size: 64 cm. This boomerang shows aboriginals interacting with missionaries and hunting emu. Also present are Queensland Bottle Trees

Details of Boomerang CH6

Size: 64 cm. This boomerang shows various animals and depictions of royalty and troopers possibly copied from books.

CH10 Incised Club

Reference Number: CH10

This beautiful old club shows a trooper making an arrest. It also shows a man in a hat with crossed arms – perhaps indicating that he has been handcuffed. It displays the cross-hatched patterns found on many early Barambah/Cherbourg Mission artifacts.

Conclusions

The study of the early transitional artifacts of Barambah/Cherbourg is still in its infancy. Until the report produced by Paul Tacon et al and the accumulation of a collection of artifacts by Scott Rainbow, the odd Cherbourg artifact that turned up was assumed to be the work of a single talented individual.

The Rainbow Collection has demonstrated that there was almost certainly a small industry at Cherbourg producing these artifacts for resale. The variations in quality, design, materials used and subject matter indicate that a number of talented artists were recording their experiences on portable objects.

Tacon et al, notes that some of the objects they examined from early museum collections had ‘degenerate modern’ written on them by past curators because they were adorned with skilfully produced and faithfully rendered figurative imagery.

R.B Phillips, notes ‘Past generations of ethnologists and art historians not only have failed to recognize the mediating role of souvenir and other transcultural arts but also have actively devalued them, damning them as acculturated and therefore “degenerate,” and as commercial and therefore inauthentic’.

The artifacts of Cherbourg are anything but ‘degenerate’. Given that most aboriginal history is transmitted orally (unlike white written history), the artifacts of Cherbourg are the equivalent of books or snapshots of aboriginal experience in the early 20thcentury and are thus an important addition to Australian history.

Scott Rainbow September 29, 2009

References

[1] Paul S. C. Tacon, Barrina South, Shaun Boree_Hooper (2003). Depicting cross-cultural interaction: figurative designs in wood, earth and stone from south-eastern Australia. Archaeology in Oceania. 38:2 pp 89-101

[2] Phillips, R.B. and C.B. Steiner (eds.). 1999. Unpacking culture: art and commodity in colonial and postcolonial worlds. University of California Press, Berkeley.