About twenty years ago there came to Yirrkala, in remote Arnhem Land, a letter addressed to the Aboriginal artist living there, written by Picasso. It said: ‘I admire and envy your art’. Since then the work of Mawalan, Madaman, Nanyin, Birrigidi, Djawa, Dawdi, Malangi, Yirrwalla and many other Yulngor artists has captured the attention of the international art world. For this is the art of a people whose occupation of this area has been established at 40,000 years or more. The art is unique, in as much as it is one of the oldest primitive arts surviving in the world today. In addition, anthropologists have long considered the Yulngor to possess the most complex social structure amongst all native peoples. This is reflected in the complexity of their art. The bark paintings, as well as being the art of the Yulngor, are also their theology, history and literature.

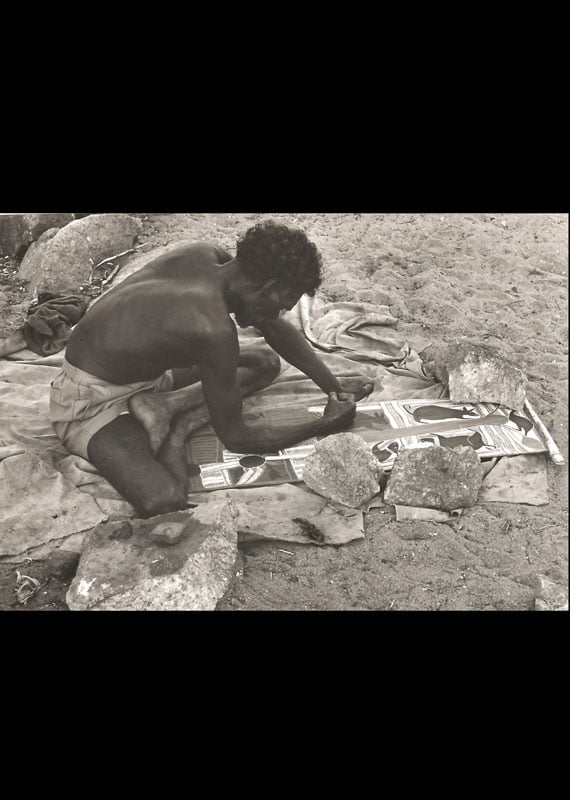

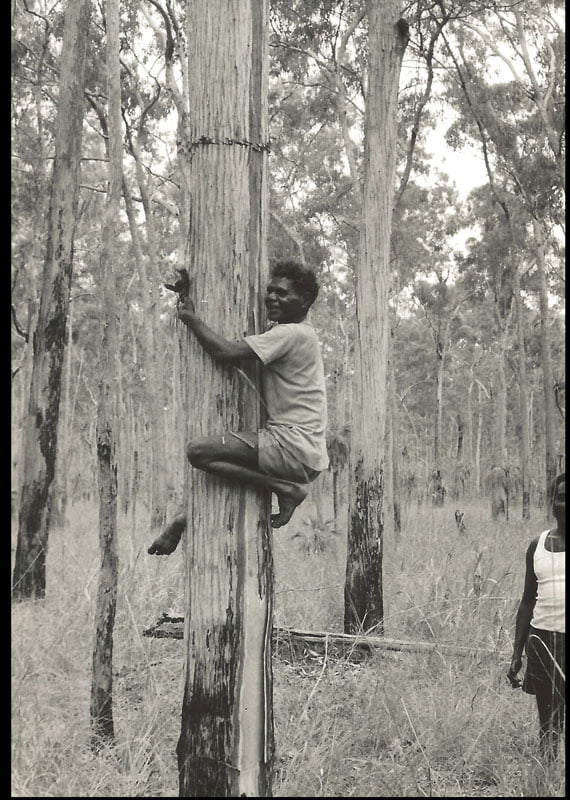

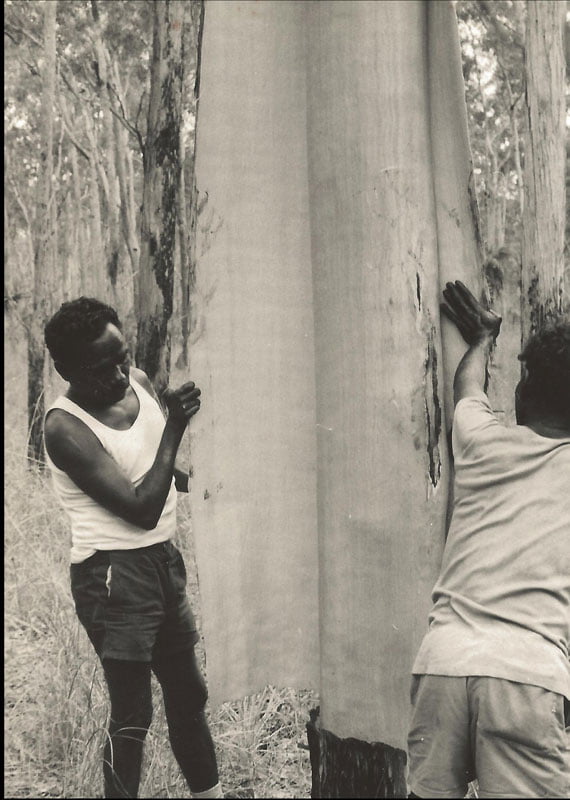

These paintings are executed on a sheet of bark, stripped from only one type of tree; the tropical Stringy Bark (Eucalyptus Tetrodontus). Immediately after the monsoonal rains, when the sap rises freely, bark is stripped from carefully selected trees. As much as a whole day can be spent in looking for a tree with the right stripping qualities. Trees are tested by stripping a narrow pierce of bark about five centimetres wide up the side of the tree. When a suitable tree is found, a top cut is made on the circumference of the tree, about six to nine meters high to wherever the first branch is encountered. A vertical cut is then made and the edges of the bark lifted, and pressure applied until it just ‘pops’ off the trunk, without any splitting, or fracturing. The bark is passed through a fire for about twenty minutes to steam it; at this stage it is very flexible and can be easily cut to size with sharp knives. It is dried in the hot sun with sand and weights on it for three weeks, and then the burnt areas are cleaned off the back with a large knife. The smooth side of the bark is rubbed with the juice of a crushed orchid bulb, a second coat of orchid juice is mixed with ochre and applied to the whole surface. When this is dry, the surface is ready for the artist. Brushes are merely a few strands of human hair, or a chewed twig, while the palettes are a slab of stone.

The pigments are ground from manganese and charcoal (black) limonite (yellow) hematite or ironstone (red) and kaolin or clay (white). The ochres are held under strict order of tribal ownership, the Dhuwa Moiety owning white and black and the Yirritja Moiety owning yellow and red. These laws are not taken lightly. Narritjin shares with Mungurrawuy complete ownership of the yellow ochre deposits near Yirrkala, which were discovered in the ‘Dreaming” by the Yirritja Goanna Man, Bitji. Ochres are traded between artists who must qualify ceremonially for the privilege of using colours belonging to the opposite moiety. Rarely are more than four colours used in a painting (sometimes only two). The aesthetics of the work depend entirely on form and design.

The works of these artists are closely linked with ceremonial song cycles and dances miming the deeds of the great spirit ancestors of the ‘Dreaming’. These spirits ancestors brought the laws to the Yulngor, and in North East Arnhem Land they brought the mala designs, gave them to the clans and told them their meanings.

As recent as fifteen years ago there were five utterly different styles, closely related to the areas in which they were produced.

Groote Eylandt

The first barks were collected on Groote Eylandt by Fred Grey and Bill Harney, in the 1920’s. They were the first white men to trade along the Arnhem Land coast.

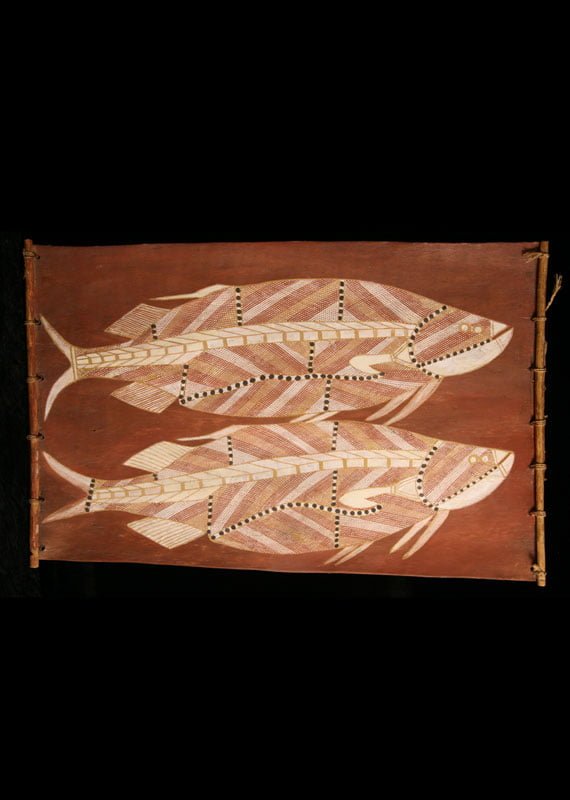

These paintings were never very big, being approximately fifty to seventy centimetres long by thirty to forty centimetres wide; occasionally one would turn up about one hundred and thirty centimetres long by sixty centimetres wide. Nearly always the background was black, as manganese was easily obtainable; in fact in many places manganese pebbles covered the ground. The designs were built up with a series of short parallel dashes and represented a variety of themes. Being animistic society, a large variety of totemic flora and fauna were depicted. Ancestral beings, sacred sites and hunting scenes were common. Very interesting abstract symbolism represented the North West Monsoon, and the South East Trade Winds.

This form of art disappeared almost overnight when mining for manganese began on a large scale in about 1966. The art produced from then on suffered a great transformation and was influenced by Aboriginal visitors from North East Arnhem Land. Until 1965, Groote Eylandt Aboriginals had lived in isolation with minimal contact from Europeans. The fortnightly DC-3 and the odd supply ship for the mission station were the only contact with the outside world. However, like other parts of Arnhem Land, there was evidence of Macassan contact and Japanese pearling luggers visited before World War 11.

Bathurst and Melville Islands

The tribes of Aboriginals living on Bathurst and Melville Islands regarded themselves as superior to the mainland people and called themselves the Tiwi, meaning ‘the people’, as a mark of superiority.

The Tiwi have lived in complete isolation from the mainland Aboriginals for an unknown period of time. This very considerable time span of thousands of years is expressed by the art forms unique to the Tiwi, by their social mores, which by comparison with the mainland Aboriginals include a higher status of women, radically different burial customs and differences in their mythology.

The time span is almost beyond comprehension. It is very evident that alien contact was practically non existent. Even mainland Aboriginals were reported to be killed if they visited these shores. However it seems reasonable, in view of the contact in North East Arnhem land, that now and again some Malay praus form Macassar in the Celebes, during the North East Monsoon, would have been blown off course and made landfall on these shores. It is certain that these visitors would have been killed or driven away. This hostility is probably the reason the Malays were unable to establish themselves on these islands, as they had done in North East Arnhem land, with a resultant cultural impact on the Yulngor of that region. The old men of the Tiwi do not remember the Malay fishermen visiting their country, and later it was believed Malay fisherman were forbidden by their serangs to go near Melville island alleging it was infected with pirates. In the early part of this century the Tiwi were still very war like, and hostile to strangers.

As a result of this long period of isolation, Tiwi art forms differ completely from the art forms found on the mainland. Although some designs on the bark paintings bear a certain resemblance to rock carvings found in central Australia, the all important sacred symbol of the concentric circle does not occur. This style of bark painting is completely abstract in form, and unlike other forms of bark paintings, it is impossible to decipher the meanings of the symbols with out the artist’s assistance. Traditional bark paintings are now only occasionally painted by a couple of old men, and are therefore very scare.

West Arnhem Land

Bark paintings in this area are closely related to the ancient cave paintings, and although the so called X-ray art has been reported among other races in the world, it is West Arnhem Land that it has reached its highest state of development. Considerable anatomical knowledge is shown by the older artists like Yirrwalla, Gabagu and Nguli Nguli. The traditional artists even showed the cross optic nerve in their X-ray paintings.

Bark paintings in this area are closely related to the ancient cave paintings, and although the so called X-ray art has been reported among other races in the world, it is West Arnhem Land that it has reached its highest state of development. Considerable anatomical knowledge is shown by the older artists like Yirrwalla, Gabagu and Nguli Nguli. The traditional artists even showed the cross optic nerve in their X-ray paintings.

In a separate class where the paintings made by the ‘clever-men’ or sorcerers showing anthropomorphic beings. These paintings were used by the men who produced them, in the practice of black magic. The painting of a’debbil-debbil’ (evil spirit) and the singing of associated chants, would ensure that the evil spirit would harm a certain individual. ‘Clever-men’ were commissioned to act on behalf of aggrieved individuals.

Astronomical bark paintings were made through out Arnhem Land, and the Aboriginals had a far greater knowledge of the night sky than most white men. This is an indication perhaps, of their deeply meditative spiritualistic philosophy, of which ample evidence is observed when in close contact with tribal Aboriginal friends of long standing.

Although now painted on bark the Mimi figures originated from the so called Mimi cave paintings consisting of artistically drown single line figure. They were depicted hunting and fighting amidst showers of spears. Some had elaborate head-dressers and carried goose winged fans, spears, woomeras and dilly bags. They main theme was man in action. When the white men asked the Aboriginals who had painted them, they replied, ‘the Mimi painted them’. Although Aboriginals did not really know the origin of the paintings, over the years a myth had developed among men that the Mimi were small stick-like people who were never seen by humans, because if approached they would blow on a rock which would open and allow them to jump inside. So the Mimi became a useful, mystical source of inexplicable events. In the rock galleries of West Arnhem Land groups of up to thirty Mimi figures may be seen engaged in battle, or hunting and are obviously the composition of one artist who has created the whole group. There is a remarkable similarity in style to the early stick figures found in Europe and Africa. Strong elements of movement and composition are evident in all of them.

Central Arnhem Land

Milingimbi, in the Crocodile Islands only a few kilometres off shore, has long been the home of such famous artists as Djawa, Dawdi, Malangi, and Dhatanggu, to name just a few. Before white contact Milingimbi was the meeting place for many clans where they assembled at the onset of the North West Monsoon to await the coming of the Macassan traders. Huge Middens of small bi-valves three meters high and seven meters in diameter seemed to indicate that large groups waited for considerable periods. Ground edge hand axes have been found in these middens and associated carbon was dated c.8, 000B.C. Milingimbi is the site of the famous ‘Macassar Well’ and many tamarind trees, around the world and along the fore shore, bear testimony to the Macassan contact.

Probably owing to the proximity of hostile people on the main land and further west, this contact was not nearly as well developed as in North East Arnhem land so the impact on the culture of the Yulngor in this area was not as significant. Although visual contact with the designs on the batik cloth led to the back ground in the paintings being fully cross hatched, this work may not indicate the moiety ownership of the design, as in the north east. Rather, it symbolises grassy plains, salt water, rocks or other natural elements. Many totemic symbols are represented, with the older artists painting symbolic mythology associated with the mortuary rites and initiation ceremonies Gupupuynggu, Liagalawumirri, Manharrngu, and Wulaki clans.

It was Malangi’s painting of the Manharrngu mortuary rites, with the great hunter Gurumarringu as the central figure, that was reproduced on the one dollar note. The Wawilak sisters and the serpent Yurlungurr dominate the Dhuwa ceremonies. Dawdi (now deceased) and Dhatanggu were the ‘Keepers’ of the secrets of these ceremonies. After Dawdi’s death, because there were no young men in the Liagalawumirri Clan who had completed the five ceremonies to raise them to Ngarra rank, the designs and symbolism he favoured have completely disappeared. This circumstance has been repeated many times throughout Arnhem Land in the past 100 years.

Dhatanggu, who relates the same mythology through his paintings by using the same symbols, expresses them in a completely different manner. The Birrikili ceremonies performed for circumcision and mortuary rites are shown in bark paintings depicting the sacred turtles, hunting shell fish in the Banyan creek, with endless variations on this theme. In the past, paintings associated with the Birrkulda, Bunimburr and Djalambu ceremonies were produced but these have not been in evidence in recent years.

North East Arnhem land

In this area the Macassan traders were completely accepted and made a deep impact on the culture. Macassan words were found in the language and it was here lippa lippa (dug out canoe) with the great Tombala (mat sail) was accepted from Macassans and spread all through Arnhem Land and down to the Gulf. It is thought that carvings in the round originated from Macassan mortuary posts. The mortuary ceremonies of the Yirritja Moiety were greatly influenced by this Macassan contact so much so that one of the most important is called Macassan prau ceremony. Old Mathaman (now deceased) when asked why this ceremony was performed said’ as the Macassan raised their sails and sailed away so the dead mans spirit has left us’. Some Yulngor returned with the traders to Macassar and some married Macassan women and the delicate Malay skeletal structure and light skin can be observed in this area today. The Captains of the praus were greatly admired and these captains wore a short tuft of beard on the chin. This custom was adopted by the Yulngor as a badge of rank permitted only to the elders when they achieved the status of ‘Older Man’. To this day it is worn only by the most senior men and known as the ‘Macassar Beard’.

Contact is most evident in the bark paintings. So impressed were the Yulngor by the designs on the batik cloth brought by the traders, that they adopted them, with modifications as back ground designs for their totemic symbols. These cross hatched backgrounds were given Yulngor significance and so passed into their mythology, becoming moiety and in some cases clan designs. The Dhuwa Moiety adopted straight and parallel lines with fine cross hatching in-between, representing the streams of sand sent sliding down the sand hills as Djalangbara by Djanda the Sacred Goanna who startled, ran away at the approach of the Djunkgawul. These spirit ancestors made land fall there, after the voyage from Baralku, the island of the dead behind the sunrise. Walu, the sun, Djunkgawul’s wife, had sent streamers of light to show the way to Djalangbra.

The Yirritja designs by contrast consist of triangles and diamonds of different forms representing fire, clouds, running water, brackish water and rocks. Recognition of the clan design becomes difficult when, in strict adherence to king ship law, a Dhuwa man has a Yirritja mother and this gives him the right to use certain Yirritja symbols in his work. The children are skin graded according to paternal linage and when a man marries he must marry across the moiety line into another clan; his children then belong to their father’s clan.