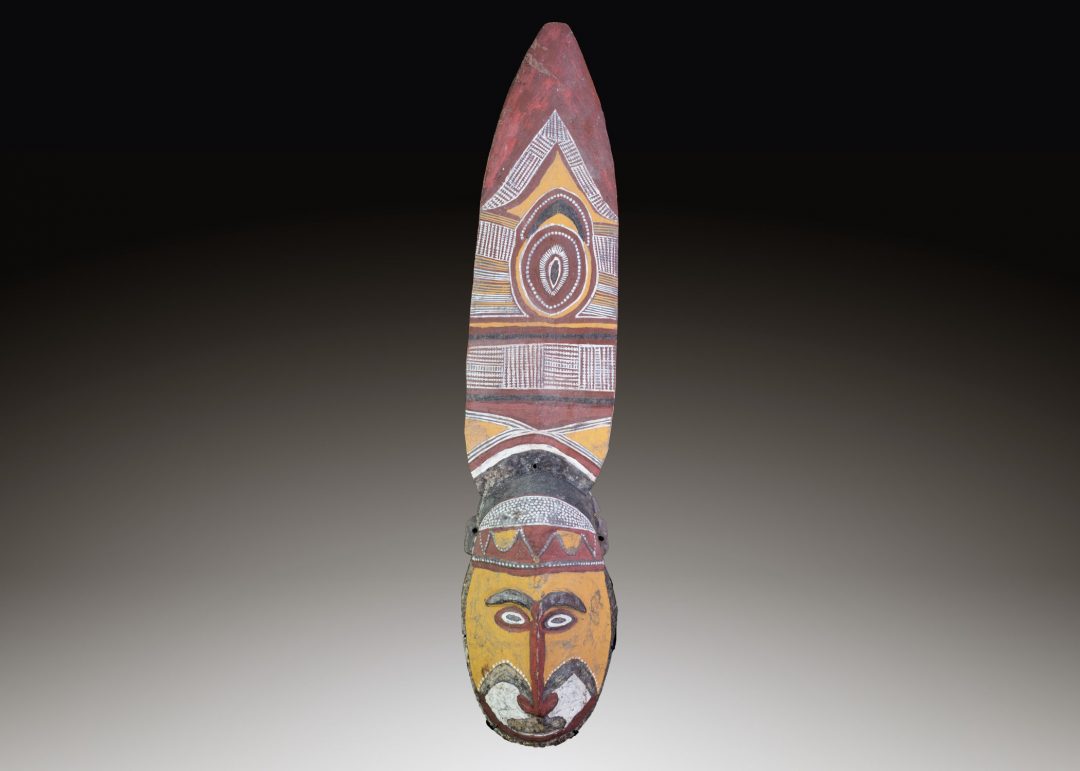

Large Canoe Splash Board (Lagim)

-

TitleLarge Canoe Splash Board (Lagim)

-

LocationMassim Region

-

Date1940s

- Size75cm (W) x 94cm (H)

-

Price$2,900.00

This is a splashboard from a kula canoe. These are ocean-going canoes (used in the kula cycle), and the splash boards sit at either end. They are intricately incised, decorated on one side only, and have slots in the back where boards are added to increase the freeboard . ( distance from the waterline to the upper deck level, ) .

Typically the splashboard is covered with abstract designs and anthropomorphic motifs. When viewed attached on a canoe, there is symmetry to these boards. The size of and shape balances with the size and shape of the canoe and outrigger.

Within the design, you can see four stylized snakes. At the ends of scrolled work, you can find highly stylized heads of frigate or sea eagles.

Along the perimeter of the splashboard are a series of holes spaced at regular intervals. This allowed for the tying of small white cowrie shells (Ovula ovum) onto this exterior border, which served both decorative and cosmological functions.

The Met Museum describes the following about the function of these boards:

“The Massim region of southeast Papua New Guinea is renowned for its ancient and ongoing inter-island exchange of shell valuables. Known as Kula, this ceremonial exchange is carried out in profusely decorated seagoing canoes carved from locally sourced trees. The most vital component of these decorative elements are the splashboards that close the dugout hull of the canoe on both ends, thereby preventing the canoe from taking in water during passage. Known as lagim in Kilivila (the language of the region within the Trobriand Islands where this piece is most likely from), splashboards are mounted with transversal wave splitboards that face forward. These are known as tabuya in Kilivila.

Projecting sideways from the prow of the canoe, a rich repertoire of motifs inhere in the complex carving style of these elaborated sculptural elements. Lagim and tabuya serve the purpose of beautifying the canoe and captivating onlookers when they arrive in the islands where the Kula ceremonial exchange takes place. The aesthetic qualities of well-executed canoe woodcarvings are believed to enchant Kula partners, “softening” their minds and making them surrender their Kula valuable shells. Splashboards also encompass a series of symbols or emblems with apotropaic qualities. They are said to ward off flying witches (yoyowa in Kilivila) that prey on shipwrecked crews, impregnating the canoes with lightness and swiftness so as to make them faster and more seaworthy. The snake emblem (mwata in Kilivila) is probably a symbol of the ancestral hero Monikiniki, considered by some matriclans in the Massim to be the initiator of the Kula exchange. The birds (susawila in Kilivila) are identified with the sea eagle: just as the sea eagle dives down to take its prey, so do tokula (Kula exchange partners) plunge upon Kula valuables.

Other, more abstract symbols are the weku and the doka. A hole at the center of one of the curving lobes, the weku stands for the voice of a bird that can be heard but has never been seen, signifying the aspiration of the tokula who will never obtain all the Kula shells that are known to circulate around the islands.

The canoe must be spelled with the right magic prior to a journey, in which case they will assist the crew if the canoe capsizes by summoning a giant fish that will take the sailors safely ashore. But if the magic used is not correct or if the canoe owner forgets to utter the spell, the ancestral heroes will turn into sharks and sea monsters in the event of a shipwreck and devour the crew.

Canoe splashboards are carved throughout the Massim region in distinctive styles roughly corresponding to the approach of carvers active in different groups of islands. They are material repositories of esoteric cognition that incorporate key elements of an otherwise oral, immaterial system of knowledge. Canoe and splashboard master carvers in the Trobriand Islands are initiated into a highly specialized and ritualized apprenticeship at a very early age. The apprenticeship lasts many years and includes learning magic spells and incantations, imbibing substances, as well as adhering to a very rigorous system of taboos that need to be observed in order to carve beautiful and efficacious splashboards (the two qualities being synonymous in Massim culture). Traditional master carvers are not allowed to draw on the wooden board they are to carve but need to incise the piece directly, using small pocket knives and repurposed pieces of iron to do it.

Further reading

Gell, Alfred ‘The Technology of Enchantment and the Enchantment of Technology’ in Jeremy Coote and Anthony Shelton (eds.), Anthropology, Art, and Aesthetics. Oxford: Clarendon Press (1994), pp. 40-63.

Malinowski, Bronislaw. Argonauts of the Western Pacific. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul (1922).

Scoditti, Giancarlo M. G. Kitawa. A Linguistic and Aesthetic Analysis of Visual Art in Melanesia. Berlin and New York: Mouton de Gruyter (1990).

Shirley E. Campbell. The Art of Kula. Oxford: Berg (2002).

This is a splashboard from a kula canoe. These are ocean-going canoes (used in the kula cycle), and the splash boards sit at either end. They are intricately incised, decorated on one side only, and have slots in the back where boards are added to increase the freeboard . ( distance from the waterline to the upper deck level, ) .

Typically the splashboard is covered with abstract designs and anthropomorphic motifs. When viewed attached on a canoe, there is symmetry to these boards. The size of and shape balances with the size and shape of the canoe and outrigger.

Within the design, you can see four stylized snakes. At the ends of scrolled work, you can find highly stylized heads of frigate or sea eagles.

Along the perimeter of the splashboard are a series of holes spaced at regular intervals. This allowed for the tying of small white cowrie shells (Ovula ovum) onto this exterior border, which served both decorative and cosmological functions.

The Met Museum describes the following about the function of these boards:

“The Massim region of southeast Papua New Guinea is renowned for its ancient and ongoing inter-island exchange of shell valuables. Known as Kula, this ceremonial exchange is carried out in profusely decorated seagoing canoes carved from locally sourced trees. The most vital component of these decorative elements are the splashboards that close the dugout hull of the canoe on both ends, thereby preventing the canoe from taking in water during passage. Known as lagim in Kilivila (the language of the region within the Trobriand Islands where this piece is most likely from), splashboards are mounted with transversal wave splitboards that face forward. These are known as tabuya in Kilivila.

Projecting sideways from the prow of the canoe, a rich repertoire of motifs inhere in the complex carving style of these elaborated sculptural elements. Lagim and tabuya serve the purpose of beautifying the canoe and captivating onlookers when they arrive in the islands where the Kula ceremonial exchange takes place. The aesthetic qualities of well-executed canoe woodcarvings are believed to enchant Kula partners, “softening” their minds and making them surrender their Kula valuable shells. Splashboards also encompass a series of symbols or emblems with apotropaic qualities. They are said to ward off flying witches (yoyowa in Kilivila) that prey on shipwrecked crews, impregnating the canoes with lightness and swiftness so as to make them faster and more seaworthy. The snake emblem (mwata in Kilivila) is probably a symbol of the ancestral hero Monikiniki, considered by some matriclans in the Massim to be the initiator of the Kula exchange. The birds (susawila in Kilivila) are identified with the sea eagle: just as the sea eagle dives down to take its prey, so do tokula (Kula exchange partners) plunge upon Kula valuables.

Other, more abstract symbols are the weku and the doka. A hole at the center of one of the curving lobes, the weku stands for the voice of a bird that can be heard but has never been seen, signifying the aspiration of the tokula who will never obtain all the Kula shells that are known to circulate around the islands.

The canoe must be spelled with the right magic prior to a journey, in which case they will assist the crew if the canoe capsizes by summoning a giant fish that will take the sailors safely ashore. But if the magic used is not correct or if the canoe owner forgets to utter the spell, the ancestral heroes will turn into sharks and sea monsters in the event of a shipwreck and devour the crew.

Canoe splashboards are carved throughout the Massim region in distinctive styles roughly corresponding to the approach of carvers active in different groups of islands. They are material repositories of esoteric cognition that incorporate key elements of an otherwise oral, immaterial system of knowledge. Canoe and splashboard master carvers in the Trobriand Islands are initiated into a highly specialized and ritualized apprenticeship at a very early age. The apprenticeship lasts many years and includes learning magic spells and incantations, imbibing substances, as well as adhering to a very rigorous system of taboos that need to be observed in order to carve beautiful and efficacious splashboards (the two qualities being synonymous in Massim culture). Traditional master carvers are not allowed to draw on the wooden board they are to carve but need to incise the piece directly, using small pocket knives and repurposed pieces of iron to do it.

Further reading

Gell, Alfred ‘The Technology of Enchantment and the Enchantment of Technology’ in Jeremy Coote and Anthony Shelton (eds.), Anthropology, Art, and Aesthetics. Oxford: Clarendon Press (1994), pp. 40-63.

Malinowski, Bronislaw. Argonauts of the Western Pacific. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul (1922).

Scoditti, Giancarlo M. G. Kitawa. A Linguistic and Aesthetic Analysis of Visual Art in Melanesia. Berlin and New York: Mouton de Gruyter (1990).

Shirley E. Campbell. The Art of Kula. Oxford: Berg (2002).